Victorian Giants: Clementina, Lady Hawarden

'Studies from Life'

Clementina, Lady Hawarden: Victorian photographer (1822-1865)

The photographic object is perishable: as Barthes explains,

it is ‘mortal: like a living organism it is born on the level of sprouting

silver grains, it flourishes a moment, then ages…Attacked by light, by

humidity, it fades, weakens, vanishes’.[1]

25 boxes of Clementina, Lady Hawarden’s photographs are now kept safely under

acid-free tissue in the V&A Museum’s Print Room. But when we see the ripped corners of her

prints, we are very aware of how close they came to being lost forever. By the late 1930s, her grand-daughter could

no longer manage the heavy albums which contained Hawarden’s life-work. She tore the photographs off the pages,

before presenting them to the Museum. In

doing so, she not only damaged many of the pictures, but also destroyed their

sequence and context. It is now almost

impossible to recover the order in which the photographs were made, or the

stories they were intended to tell.

And if the papery print is mortal, so is the person

contained within it. The girls who are lovingly watched by their mother,

complicit, aware of their part in the performance of youth and beauty, are long

dead. They are now only to be found, to use Barthes phrase, in ‘this image

which produces Death while trying to preserve life’.[2] For Barthes, the punctum brings the viewer face to face with the passage of

time. The liveliness of Hawarden’s sitters

appears to contradict this. We are

struck by their spontaneity and their playfulness before the camera.

But, in the same breath, we are aware of the

paradox that their delightful posing can now only be enjoyed in the hush of a

museum, or on a computer screen. The

young women have gone, the house has gone, only the fragile photographic paper

survives.

Hawarden made the majority of her photographs in her home in

South Kensington. The newly-built

townhouse at 5 Princes Gate was filled with her family of eight daughters and

one surviving son. Throughout her career

as a photographer, Hawarden was almost constantly pregnant: she had her first

child Isabella Grace in 1846 and her youngest daughter was born in May 1864.

Yet very few of her pictures represent a conventional family interior. A stereoscopic image of two of her girls

stands out from the collection precisely because of its apparent

normality. [Figure 1, V&A PH.457:499-1968]

Isabella Grace is seated in a tub chair, and young Clementina is on a low

stool. One is reading and the other sewing.

They are shown in an unostentatious morning room, with prints above the

fireplace. These pictures within pictures

hint at the artistic connections of the family.

The landscapes are etchings by Seymour Haden, in an advanced Whistlerian

manner, but there is also a popular print of cherubs from Raphael’s Sistine

Madonna.

This photograph places Hawarden firmly within her mid-Victorian

context. Her daughters are spending

their time in suitable feminine occupations.

Yet this ordinariness is undermined by the extraordinary fact that we

know their mother is standing behind a camera in the corner of the room. She has chosen to record this moment, in

duplicate, to be looked at later in a stereoscopic viewer that will make the

whole scene appear in 3-D. The

complicated doubling and playing with perception is heightened by the girls’

clothes. They are wearing identical

dresses with fine dark stripes on a white background, and contrasting cuffs and

hems. The stripes of their dresses are

at odds with the ivy patterned upholstery on the chair and the insistent

diamonds of the carpet and wallpaper. The girls keep their eye on their work, so

we can study them in profile.

This interior, which corresponds in many ways to the

expectations of orthodox Victorian taste, has been made queer or peculiar by

Hawarden’s decision to freeze it on the prepared plate of her camera. She encourages us to study it, to note how the

focus shifts from one lens to the other, to dwell on the folds of the matching

dresses, and to try to resolve the design of the wallpaper. But this is not an

experiment she cares to repeat. The

majority of her photographs are taken in bare rooms, set with props and

screens, or in the open air in Ireland.

A large area of Hawarden’s home was given over to her

work. Two interconnected rooms on the

first floor became her studio.[3]

In most houses, these would have been

entertaining spaces – possibly the drawing room and dining room - but Hawarden

and her family decided to devote them to her photographic practice. Evidently

her photography was more than a hobby to fill quiet moments. It required space, time and money.

Judging from the different prints remaining

in the V&A Museum and a few other scattered examples, Hawarden worked with

at least seven different cameras. These

would have been expensive pieces of equipment, cumbersome to set up, and

awkward to store. And her supplies of

chemicals would also have to be given house-room.

Hawarden

left no written record of her processes.

We have to look closely at the photographs themselves to find clues to

her working practice and her intentions. A portrait of young Clementina with

stained fingers, and wearing a dark apron over her dress, demonstrates that

making photographs was a messy business. [figure 2, V&A PH.457:319-1968]

It also suggests that at least one of Hawarden’s daughters helped her in preparing and developing the plates. It is likely that the dark room was on the same floor as the studio spaces. There was a large windowless space that connected the two light-filled rooms; this was usually screened off while Hawarden was working. The darkroom would have required a good water supply. When Julia Margaret Cameron developed her prints, she wrote that she needed ‘nine cans of water fresh from the well’ to complete each one.[4] Hawarden, using a similar wet collodion process, must have taken this into account when she chose the layout of her studios.

When the family first moved into Princes Gate, the rooms set aside for photography had bare walls. However, towards the end of the 1850s, they were decorated with distinctive patterned wallpaper, which featured as a background to many of Hawarden’s studies. In the photographs, the pattern reads as black stars on a pale background. However, in reality, as Charlotte Gere has pointed out, the paper was printed with deep gold flowers, their pointed petals making them seem star-like. The wall covering was heavy and expensive, and was fixed to batons.[5] Hawarden discovered that the starry background was distracting in some compositions. So she had a screen made, which could be fixed behind her sitters. Judging from the gaps visible low down in the screen, it was made of painted wood and fitted onto a moveable base. Occasionally, both the blank screen and the starry paper were included in the composition. In a study of Isabella watching over a sleeping young Clementina, the visual shift from the screen to the wallpaper is elided with some muslin drapery [figure 3, V&A PH. 255-1947].

It also suggests that at least one of Hawarden’s daughters helped her in preparing and developing the plates. It is likely that the dark room was on the same floor as the studio spaces. There was a large windowless space that connected the two light-filled rooms; this was usually screened off while Hawarden was working. The darkroom would have required a good water supply. When Julia Margaret Cameron developed her prints, she wrote that she needed ‘nine cans of water fresh from the well’ to complete each one.[4] Hawarden, using a similar wet collodion process, must have taken this into account when she chose the layout of her studios.

When the family first moved into Princes Gate, the rooms set aside for photography had bare walls. However, towards the end of the 1850s, they were decorated with distinctive patterned wallpaper, which featured as a background to many of Hawarden’s studies. In the photographs, the pattern reads as black stars on a pale background. However, in reality, as Charlotte Gere has pointed out, the paper was printed with deep gold flowers, their pointed petals making them seem star-like. The wall covering was heavy and expensive, and was fixed to batons.[5] Hawarden discovered that the starry background was distracting in some compositions. So she had a screen made, which could be fixed behind her sitters. Judging from the gaps visible low down in the screen, it was made of painted wood and fitted onto a moveable base. Occasionally, both the blank screen and the starry paper were included in the composition. In a study of Isabella watching over a sleeping young Clementina, the visual shift from the screen to the wallpaper is elided with some muslin drapery [figure 3, V&A PH. 255-1947].

Of the two main rooms in which Hawarden took her photographs,

one looked out onto the road, and the other faced the garden that was shared by

the residents. The back room had sash

windows and a shallow balcony, while the front room was fitted with casement

windows. The family could step through

these windows onto a terrace. The liminal open spaces – attached to the house,

yet sunny and semi-public – became important elements in Hawarden’s

compositions. Like the painters Berthe

Morisot and Mary Cassatt, Hawarden discovered that the balcony and the terrace

were rewarding sites for female artistic production.

Hawarden was a woman regularly ‘in confinement’ because of her

child-bearing. Yet she found expressive

ways of piercing the formal boundaries of her home as her daughters moved

delightfully between interior and exterior.

The windows, elevated outdoor spaces and even the backdrop of houses

across the square all became part of her choreographed landscape of the

imagination. She bounced reflections off

panes of glass at queer angles. She

encouraged shafts of light to make luminous geometry on walls and floor. She moved chairs, girls, dogs and carved

wooden owls onto the terrace to form odd interactions. [figure 4, V&A PH.

302-1947] She posed her curved and flounced daughters against the insistent regularity

of other people’s houses.

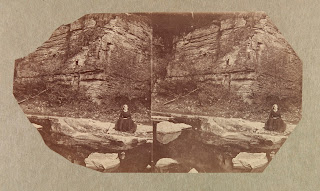

In Ireland she had more room to play with. On her husband’s estate at Dundrum, Hawarden

photographed farm workers and animals. She set up an outdoor studio against the

wall of a workshop to experiment with portrait compositions. She also took a stereoscopic camera into a

river valley to photograph a young woman. [figure 5, V&A PH.457:49-1968]

This figure is dwarfed by the cliffs behind

her, with sharp marks of cut stone clearly visible on their surface. The river reflects back fallen rock, rock

face, and the thoughtful girl who refuses to read the book in her lap. The

whole scene is again doubled by the stereoscopic lenses. Her young model is balanced between confinement

and release. She appears trapped between

the stones that completely fill the background and the water at her feet. However her gaze, up and out of the image,

suggests other means of escape: perhaps by creating an image in her mind’s eye,

perhaps by the inspiration of a passage in her book, perhaps even by plunging

through the mirrored surface of the water and into the unseen depths.

Hawarden created a similar sense of alternative realities,

beyond the picture plane, in other photographs taken outdoors in Ireland. Her

study of a young woman walking away from us, under a canopy of trees, is one

example [figure 6, V&A PH.457-1968:149].

The figure is seen from the

back. Her skirt is kilted up, in dark

folds of fabric, revealing a pale hooped underskirt. This may be practical – to save her dress

from the dusty road – but it adds an uneasy element to the scene. It implies exposure, vulnerability. It draws attention to the sway of the woman’s

body, and to the delicate play of light and shade throughout the

composition. As her feet are hidden in

the shadow of her skirts, she almost seems to hover above the surface of the

track. She is about to pass away from

us, around a corner and into the picture, beyond our reach.

Back in London, Hawarden had less room to manoeuvre. She and her daughters could not roam about with cameras and hitched-up skirts as they did on their private lands in Tipperary. But they did nibble away at the boundaries of convention. Hawarden manipulated the codes of Victorian femininity to her own ends. Often she placed her young women deliberately on the threshold of the public spaces: in one photograph, a gate in the balustrade of the terrace has swung open. [figure 7, V&A PH.457-1968:443]

This barrier between public and private has always, in other images, seemed impermeable. But this picture makes it clear that the girls could step out and down into the communal space of the square. Hawarden photographed her daughter in no-man’s-land, leaning on the ledge of the balustrade, poised between home and the wide world.

Back in London, Hawarden had less room to manoeuvre. She and her daughters could not roam about with cameras and hitched-up skirts as they did on their private lands in Tipperary. But they did nibble away at the boundaries of convention. Hawarden manipulated the codes of Victorian femininity to her own ends. Often she placed her young women deliberately on the threshold of the public spaces: in one photograph, a gate in the balustrade of the terrace has swung open. [figure 7, V&A PH.457-1968:443]

This barrier between public and private has always, in other images, seemed impermeable. But this picture makes it clear that the girls could step out and down into the communal space of the square. Hawarden photographed her daughter in no-man’s-land, leaning on the ledge of the balustrade, poised between home and the wide world.

In other compositions, Hawarden played with melodramatic

notions of confinement and interiority.

She and her girls rigged up elaborate muslin drapes across the

windows. Some were plain, others

sprigged with ivy-leaves, bringing the outside in. [V&A PH.457: 150-1968

and PH.457: 344-1968]. These semi-transparent swags of material became players

in a game of hyper-femininity, as young Clementina grasped, crumpled and

twisted them in her out-stretched hands. In one reading of these images, she appears to

be protesting against the limitations of the domestic sphere, and the

restrictions imposed upon Victorian girls.

However, the very fact that she was modelling for her mother, and that

they were both complicit in the exaggerated posturing, undermines this

interpretation. Both Clementinas, mother

and daughter, were collaborating in an undomestic, though private, space. This was no claustrophobic, tight-lipped drawing

room scene. These images were created in

a light-filled studio. The floors are plain, the boards sometimes left bare,

and sometimes covered with rush matting.

There are scraps of paper left lying about. Objects are out of place.

This was a utilitarian space, with none of the upholstery and carpeting seen in

the morning-room stereoscopic photograph.

Hawarden’s women are inside a

Victorian home, but it is unheimlich.

[1]

Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida, p.93

[2]

Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida, p.92

[3]

See Virginia Dodier, Clementina, Lady Hawarden: Studies from Life 1857-64,

V&A Publications, London, 1999 p.120 for a floor plan of Princes Gardens

[4]

Julia Margaret Cameron, quoted by Colin Ford, Julia Margaret Cameron: 19th

Century Photographer of Genius, National Portrait Gallery, London, 2003, p.39

[5] I

am grateful to Charlotte Gere for pointing this out during our discussions at The

Gendered Interior in Nineteenth-Century Art symposium on 20 November

2013.

Comments

Post a Comment