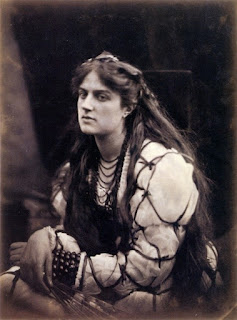

Julia Margaret Cameron and 'Hypatia'

1868: The Isle of Wight

Two women walk across the lawn towards the glasshouse. They do not stop to admire the sea-view. Hurriedly, huskily, one explains her purpose

for the morning. Her dark skirts bob over the grass as she side-steps the

dishes of chemicals that litter the lawn. Her younger friend follows more

cautiously. Her dress is white,

cumbersome and criss-crossed with ribbons.

She is weighed down by jewellery; an outlandish bracelet winding around

one wrist, a web of necklaces at her throat.

Her hair is caught up in combs at each temple, and then it flies

loose. It is rather a nuisance, tangling

in the breeze from the shore, but Marie does not bother to mention it. It would make no difference. When Julia Margaret Cameron is in full flow,

she will not be swayed by small inconveniences.

It is the late summer of 1868 and a perfect morning for

taking photographs. Marie Spartali is

playing the part of Hypatia, mathematician and philosopher of ancient

Alexandria. Julia Margaret Cameron is in

her working clothes. Her sleeves and

skirts are spattered with chemicals.

Blotchy blacks and purples mark where nitrate of silver has dripped off

the glass negatives and onto her dress.

As Julia likes to tell her visitors, ‘I turned my coal-house into my

dark room’[1],

and her glazed studio was once the chicken shed. In this topsy-turvy setting, Julia works her

magic.

Marie Spartali is a professional model, and a painter

too. She understands the habits of the

artist’s studio, the etiquette that usually separates the domestic and

professional. But Julia’s way of working

is idiosyncratic. The whole Cameron household is caught up in Julia’s

enterprise. A girl is waiting by the glasshouse. Julia has trained her staff to work on both

sides of the camera. So, in addition to

their indoor duties, cleaning, mending and serving at table, Julia’s maids are

also her models and her technicians. One

of her servants, Mary Ryan, has recently left Julia’s service to marry a young

man in the India Office. The Camerons

had found her, as a child, begging on Putney Heath. They took her in, taught her to read and

write. And to pose. Julia’s close-up photographs of her young

maidservants delight in their teenage softness, their dreamy eyes and abundant

hair.

Julia Margaret Cameron has created something extraordinary

at her home on the Isle of Wight. Not

only does she conjure pictures with her stained hands, she shows how women

might live – differently and fully. To

the girls who come to her – servants, visitors, stray tourists who are swept

into the garden to sit before her camera – she is a revelation. Julia is subversive, generous, untidy,

wilful. She dresses in flowing red velvet, loves curry and speaks fluent

Hindustani. She is often short of cash and always chasing the beautiful.

Mrs Cameron started taking photographs in earnest in the New

Year of 1864, when she was 48 years old.

Her children were growing up, marrying and leaving home: ‘for the first time in 26 years I am left without

a child under my roof’, she explained.[2]

Her husband was in Ceylon overseeing the family coffee plantations. And so her

daughter thought ‘it may amuse you Mother to try to Photograph during your

solitude at FreshWater’[3].

Julia’s first camera was a gift from woman to woman, from a bride to her

mother.

Since the earliest days of photography, Julia had been

fascinated by this new medium. She was

already married and living in India in 1839, when William Fox Talbot and Louis Daguerre

both announced that light and shade could be fixed on glass. Through her friendship with the scientist Sir

John Herschel, Julia followed each new development. Their correspondence crossed oceans. As she reminded Herschel later, ‘the very

first information I ever had of Photography in its Infant Life of Talbotype and

Daguerreotype was… in a letter I received from you in Calcutta’.[4]

From their letters it is clear that that photography was an

unladylike occupation. Still Julia

persevered. Her camera and tripod were bulky and awkward. The glass plates

which she slid, wet, into the body of the camera were over a foot square.

Smearing syrupy collodion onto the glass to create a photosensitive surface was

a messy business. Developing the prints

required gallons of water: Julia said she needed ‘nine cans of water fresh from

the well’ for each photograph.[5] (That was a job for the maidservants.) And finally the excess chemicals were removed

using potassium cyanide. This was not

only messy and smelly but dangerous. She asked Herschel in 1864, ‘Is it such a

deadly poison – need I be so very afraid of the Cyanide in case of a scratch on

my hand?...Are any of the Chemicals prejudicial to health if inhaled too

much?’ Herschel was concerned ‘about

your free use of the dreadful poison …letting run over your hands so profusely

– Pray! Pray! Be more cautious’. [6] But Herschel knew Julia well enough to

realise that she was anything but cautious.

She launched herself into her artistic career with

gusto. Her ‘first perfect success’ was a

portrait of Annie Philpot. The little

girl is unsmiling, sitting in her coat – it was late January – in three-quarter

profile. Julia was so delighted that she gave it to Annie’s father immediately. She wrote an excited note explaining how the

photograph was ‘taken by me at 1pm Friday Janr. 29th Printed – Toned

– fixed and framed all by me’. She began

the sitting in the crisp winter sunshine, and finished the print that evening

by lamplight. Within two years she had a

one-woman exhibition in London at Monsieur Gambart’s French Gallery. 146 prints and glass negatives were on sale

for five to ten shillings. She offered a

special discount to artists. She threw herself into the quickening art-world of

the 1860s, making sure her work was visible to painters and literary men. She

sent out parcels of photographs to those she hoped to entice into her

studio. She pursued Tennyson until he

succumbed, and the reluctant poet was led into the glasshouse. In Julia’s words, the resulting portrait was

‘A column of immortal grandeur – done by my will against his will.’[7]

She photographed her famous men nearly life-size. She tousled their hair, illuminated the lumps

and bumps of their foreheads, and encouraged them to ‘look at something beyond

the Actual into Abstraction’.[8] This far-away look may be more to do with the

long exposures than with the profundity of their thoughts. Julia made her sitters hold their pose for up

to seven minutes before releasing them back into the garden. If they giggled or

fidgeted, the whole exposure was ruined.

Even if they behaved themselves, the large scale on which

she worked meant that the details in some parts of the photograph were sharper

than in others. Julia used this to her

advantage. Her portrait heads seemed to

emerge from a mist.

Julia Margaret Cameron experimented with the latest

technology to create parables, poems and annunciations. She created a

light-suffused aura around the beautiful women who sat for her. And she was adamant that no-one should treat

her as an amateur. She manipulated,

sometimes she got fingermarks on her plates.

But she knew what she was doing: ‘What is focus?’ she asked Herschel,

‘and who has the right to say what focus is the legitimate focus?’.[9] Julia did not value crisp, scientific

shots. She wanted her images to rival

the paintings of her Pre-Raphaelite friends.

She admired the shimmering outlines of Gabriel Rossetti’s ‘stunners’,

his portraits of girls with luxuriant hair and full lips. She sent Rossetti copies of her favourite

prints, hoping to entice him to Freshwater.

He never came. But he thanked her

for ‘the most beautiful photograph you so kindly sent me.’ And then he added, ‘It is like a Lionardo’.[10] This was the highest possible praise. Leonardo da Vinci was the ultimate artist,

the master of subtlety and ambiguous beauty.

Julia could not be happier.

So she had set herself the task of making more pictures

worthy of a great artist. On this bright

autumn morning in 1868, Julia would revive the memory of Hypatia. A scholar in

dying days of the Classical world, Hypatia was a potential role-model for

Victorian women who sought new ways of expressing themselves. She was brave,

clever and pagan. But her story had no happy ending. As a teacher and thinker,

she defied the Christian hierarchy and suffered a horrific death. She was stripped, mutilated, martyred on the

very steps of the altar by order of the Patriarch of Alexandria. In the words

of Edward Gibbons, ‘her quivering limbs were delivered to the flames’.[11]

Gibbons’ account of her torture was prurient, verging on the

erotic. But Julia Margaret Cameron saw it differently. Her desire was to rescue Hypatia from such

voyeurism. She would be shown as a

thoughtful woman, a dignified woman, a woman with a voice. In life, Hypatia did not hold her

tongue. She refused to marry. She was a scientist. This is what concerned Marie Spartali and

Julia as they began to make the photograph – a woman who chose her own path,

regardless of risk. And so the maid drew

water from the well. They prepared the

plates. They set up a head-rest for the

long exposure. Marie picked up her fan,

gathered her skirts and took her seat before the camera’s Cyclops eye. She sits before us now. Her chin is lifted,

and she looks out, and through us, and into the world beyond the frame.

[1]

Julia Margaret Cameron, quoted by Brian Hinton, Julia Margaret Cameron

1815-1879: Pioneer Victorian Photographer, Julia Margaret Cameron Trust,

2008, p.5

[2]

Julia Margaret Cameron, letter to William Michael Rossetti, 1866, quoted by

Colin Ford, p.61

[4]

Julia Margaret Cameron, letter to Sir John Herschel, 1866, quoted by Colin

Ford, p.35

[5]

Julia Margaret Cameron, quoted by Colin Ford, p.39

[6]

Correspondence between Julia Margaret Cameron and Sir John Herschel, 1864 &

187, quoted by Colin Ford, p.39

[7]

Julia Margaret Cameron, quoted by Colin Ford, p.50

[8]

Edward Fitzgerald, quoted by Colin Ford, p.46

[9]

Julia Margaret Cameron to Sir John Herschel, 31 December 1864,

[10]

Dante Gabriel Rossetti to Julia Margaret Cameron, January 1866, quoted by Colin

Ford, p.70. Over the next decade, Rossetti

collected at least 41 photographs by Cameron, including a copy of Hypatia.

[11]

Edward Gibbon, The History of the

Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, vol. 5, AD 413-415, pubd London: Henry G Bohn, 1854, p.213

I love the photos and history of Julia Margaret Cameron, Ms. Cooper! Would you possibly be interested in writing a guest article on her for the Carolinian's Archives Once Upon a History pages?

ReplyDelete